You are now reading part 4 of the comprehensive strength training guide that teaches you the A - Z of building muscle and strength through articles that are easy to understand. Click here to see all the articles in the guide.

Have you ever heard about Norway? You probably have, as the nation does extremely well in some sports. You may be thinking of cross-country skiing or women’s handball.

However, Norway also does really well in a completely different sport. The sport of lifting iron until blood vessels pop.

The sport where competitors have lifted a combined weight equivalent to that of a small African elephant by the end of the competition day. The sport I am talking about is, of course, powerlifting.

And I think that’s pretty impressive. A small nation like Norway manages to be one of the best in the World in such a sport, with extremely strict, and more often than not unannounced, doping controls throughout the year.

How can that be?

One important factor is the excellent researchers and professors at the Norwegian School of Sport Sciences and Olympiatoppen (an organization that is part of the Norwegian Olympic and Paralympic Committee and Confederation of Sports).

Researchers like Gøran Paulsen, Truls Raastad, Bent Rønnestad, Alexander Wisnes, and the late Per Egil Refsnes have made a great theoretical and practical effort to elevate the sport.

Several of these were in collaboration with the Norwegian Powerlifting Federation for the secret Frequency Project, which I will reveal and analyze a little later in the guide.

There is also another important factor at play. I remember a time when powerlifting was of great interest to me (it of course somewhat still is). There was one name that continuously came up in almost all settings: Dietmar Wolf.

Dietmar is a former national team coach for Norway in powerlifting and is legendary in the industry. The fact that he kept his cards close to his chest probably had a lot to say. Many have wondered how the small nation of Norway could do so well in this sport – and many have tried to uncover the secrets.

The secrets of Dietmar.

Those who have tried this have largely done so by analyzing some of the programs he created. The programs are still online, for those who want to have a look.

When I downloaded one of his programs many years ago, I remember noticing one particular thing.

The program was created in Excel and summed up the total training load for each workout. This was done by multiplying the number of sets, repetitions, and the weight used in a given exercise.

This is one of many ways to define training volume. But is it the best for us mere mortals who just want to get stronger and build muscle as efficiently as possible?

How to define training volume in a good way

Earlier in this guide, I mentioned that you must stimulate the muscles sufficiently, but no more than that. What does that really mean? How much stimulation is adequate?

This is where training volume as a concept enters the game. It helps us to make sure that the muscles get enough stimulation, but not too much.

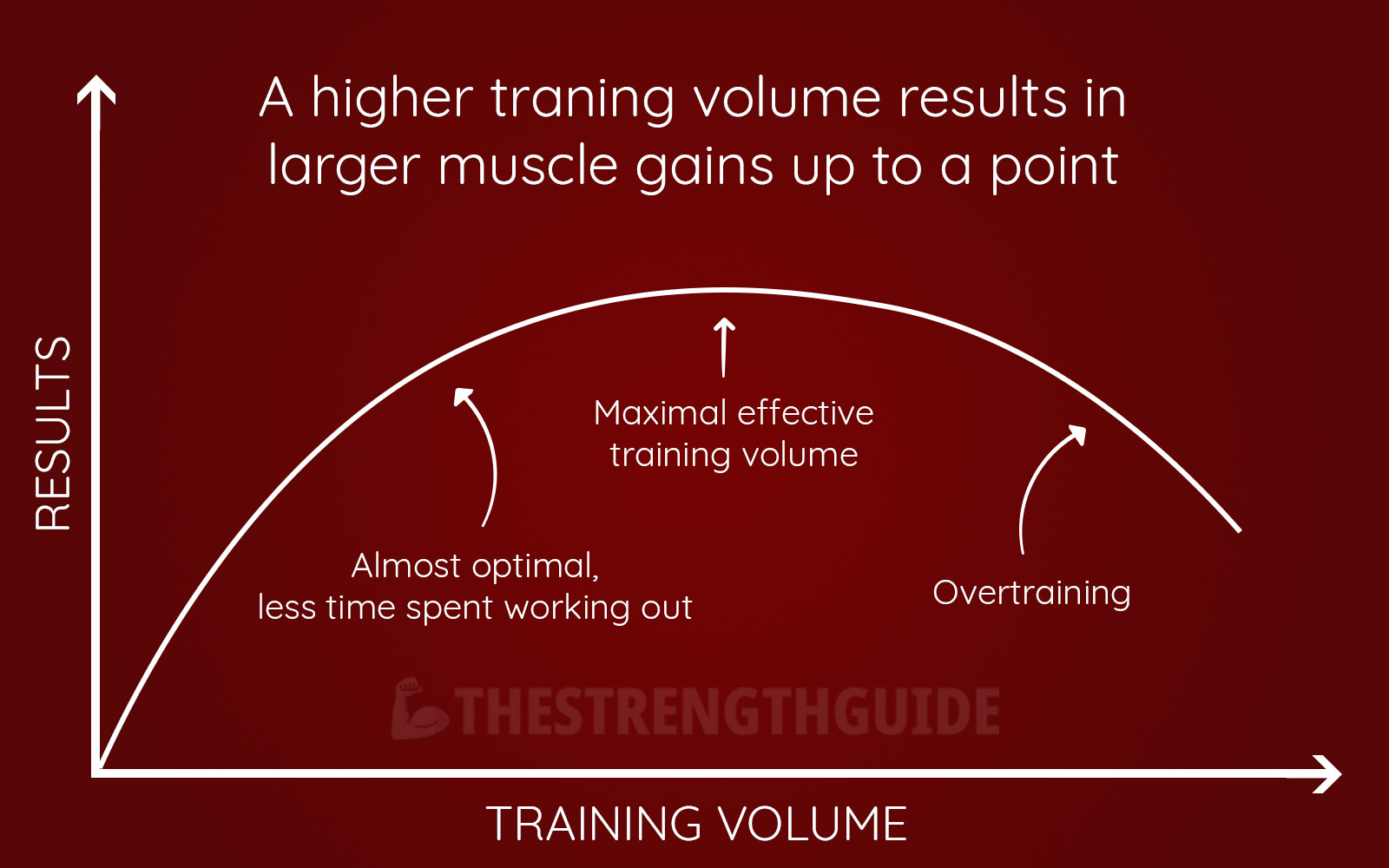

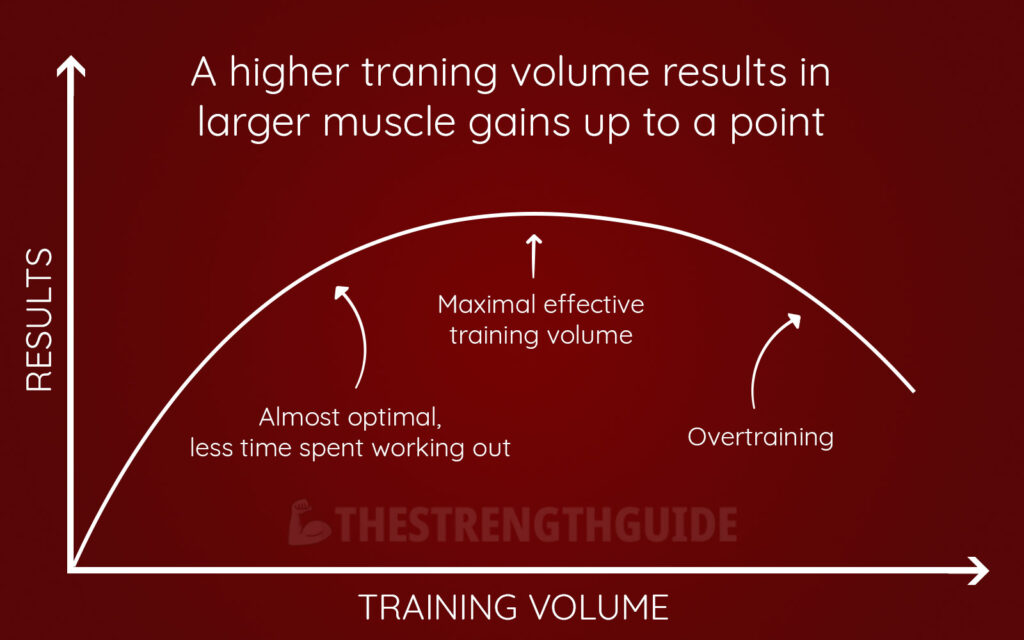

Training volume is the total stress you put your muscles through strength training. A higher weekly training volume gives better results (up to a certain point) as long as you manage to recover between each workout.

You may have read about this before. In my opinion, there are too many different definitions out there. If you do a quick search to find out what training volume actually is, it’s almost impossible not to get totally confused.

Researchers have many different ways of measuring training volume, and the occasional internet guru may have come up with even more.

Is training volume the number of sets per week? Or the total number of repetitions per week? Or just the total number of repetitions in sets where you go to failure? What about sets multiplied by repetitions? Or maybe we should use Dietmar’s definition and multiply repetitions, sets, and weight?

You might go crazy trying to figure it out.

It’s even more unfortunate that only one of these definitions includes what we wish to achieve when we train to get stronger.

Namely, the activation of the motor units associated with the muscle fibers that have large growth potential. This is something that you learned about earlier in the guide.

Based on many of the definitions, it is easy for me to achieve a very high training volume without gaining a single gram of muscle mass.

I’ll just lie down and bench press the bar a hundred times. With the bar weighing 20 kg, I am fine lifting it a hundred times. If I do 4 sets, then we have the following training volume in bench press:

20 kg x 100 repetitions x 4 sets = 8000 kg

You can easily see the problem when we compare this with the equivalent number of sets with 100 kg on the bar, where I only manage 5 repetitions:

100 kg x 5 repetitions x 4 sets = 2000 kg

Which training method do you think builds the most muscle? I, for one, would not put money on it being the method with the highest defined volume.

Therefore, we need a way to measure training volume that takes training intensity into account, so that we know that the volume we are doing is “effective volume.”

A smart approach is to count the number of stimulating repetitions per muscle. You should do this per session and week.

A stimulating repetition, also known as an “effective repetition”, is a repetition in which all motor units are activated while the lifting speed is low. This ensures high mechanical tension in the particular muscle fibers that grow a lot after strength training.

The concept has been around for a long time, but as far as I know, it was Børge Fagerli who first put it into practice with his Myo-Reps protocol.

Later, the concept was also presented and refined by Carl Juneau and Mike Israetel, before Chris Beardsley came up with his own version.

I present here my interpretation of the concept of stimulating repetitions based on the work done by these people, as well as criticisms of the concept that have been made by other knowledgeable researchers in the field.

Training volume defined as stimulating repetitions

Let’s go back to the example I gave which shows that doing 100 repetitions of 20 kg gives greater total weight lifted during a workout than doing 5 repetitions of 100 kg.

As mentioned, I can bench press 20 kg all day without getting any effect from the exercise. But I still do a lot of repetitions.

So it may seem that none of the repetitions I have done contributed to muscle growth. So none of the repetitions were stimulating.

Also, if I lift 5 repetitions with 100 kg on the bar, I will experience muscle growth and an increase in strength. Then at least some of the repetitions were stimulating.

So the question is: how you can know which repetitions stimulate muscle growth, and which do not?

Here is where it unfortunately gets a little complicated. But let’s make an honest attempt at understanding this!

In the article about how muscles work, you learned that lifting at 80-90% of your max lift (1RM) is the threshold to activate all the available motor units.

Studies show that you can lift between 7 and 12 repetitions at this intensity. Does that mean that all the repetitions in a set of 12 repetitions are stimulating?

It might be easy to think that they should be. However, do you remember that high muscular activation does not necessarily mean high mechanical tension?

This means that we can’t state that muscle growth will happen as long as muscular activation is maximal during a repetition. Studies also show this in practice.

How many stimulating repetitions are there in a set taken to failure?

Let’s dive into the research. What do we actually find in studies that try to find a link between training volume and muscle growth? What relationship exists, exactly?

It turns out that only the number of sets done to failure affects muscle growth. The higher the volume defined as the number of sets to failure, the more muscle growth occurs. Up until a certain point, of course.

If we define training volume as the number of sets multiplied by repetitions or weight, then there is no correlation. For example, one study showed that a low volume produced just as much muscle growth as a high volume when training volume was defined this way.

The reason is that the groups did the same number of sets done to failure, but one group lifted lighter weights and did more repetitions. Thus, they got a higher volume defined as set times repetitions or weight, but not when training volume is defined as the number of reps done to failure.

This does not mean that you should always train to failure, which you will learn more about in the article on training intensity later in this guide.

Only a higher training volume defined as the number of sets taken to failure leads to greater muscle growth and more strength after strength training, compared to lower training volumes.

In other words, research shows that a set of 10 repetitions results in the same amount of muscle growth as a set of 20 repetitions if they are both taken to failure. Thus, we can assume that only the last few repetitions in such a set give the effect we are looking for.

But is it the last 2 repetitions? Or maybe the last 6?

Let’s look at research that has conducted such “exhaustion sets” with different numbers of repetitions. In the following, when I mention doing sets, I am talking about sets taken to failure. I also use the words failure and exhaustion interchangeably.

Perhaps we can find a point where doing more repetitions will not give more muscle growth. The limit for the number of stimulating repetitions in a set will likely be around this point.

Research shows that training 3 sets of 1 repetition at 1RM gives little muscle growth. It is probably safe to assume that such a workout involves 3 stimulating repetitions, i.e. 1 per set since you are lifting as heavy as you possibly can in the exercise.

Furthermore, research shows that training with 2 – 4 repetitions per set gives less muscle growth than training with 8 – 12 repetitions per set.

There are also studies showing that we can compensate for a low number of repetitions in each set by doing more sets.

One study also had subjects stop their sets before reaching exhaustion. On average, they stopped 4.4 repetitions before they would actually fail. The subjects experienced some muscle growth after doing many of these sets.

This suggests that the number of stimulating repetitions is at least above 4 since they could have done at least 4 repetitions more when they stopped.

Based on the available research, it is safe to assume that there are between 5 – 8 stimulating repetitions in a set taken to failure.

The number is most likely closer to 5 than 8, and we can therefore say that there are 5 stimulating repetitions in a set taken to failure to be on the safe side.

This means that if you perform a set of 10 repetitions. then only the last 5 repetitions – numbers 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10 – will stimulate muscle growth.

If you do a very heavy set of 3 repetitions, all of them will be stimulating. However, you could achieve a better effect by lowering the weight and achieving 5 stimulating repetitions in the set.

It is safe to assume that it is the last 5 repetitions of a set taken to failure that stimulate muscle growth.

Therefore, 3 sets of 10 repetitions and 3 sets of 25 repetitions, both taken to failure, should give the same amount of muscle growth, since both give 15 stimulating repetitions in total.

Similarly, training with 4 sets where you leave one repetition in the tank should give more muscle growth than 2 sets done to failure.

The former method provides 16 simulating repetitions:

4 sets x 4 stimulating repetitions = 16 stimulating repetitions

The latter method gives 10 stimulating repetitions:

2 sets x 5 stimulating repetitions = 10 stimulating repetitions

By not training until muscle failure, you can make up for the missing stimulating repetitions by doing additional sets, as each repetition you leave in the tank results in one less stimulating repetition. You can learn more about this in the article on training intensity later in this guide.

How many stimulating repetitions are sufficient?

Now you know you can control the training volume per workout session by adding up the number of stimulating repetitions you perform.

But what is the ideal amount of training volume? How many stimulating repetitions should you do per muscle per session? And how many stimulating repetitions should you do per week?

Let’s start with talking about how high your training volume should be per individual workout. The answer to this question is very complex and requires a more in-depth examination to fully explore.

There have been conducted many studies with both strengths and weaknesses we need to take into account when figuring this out.

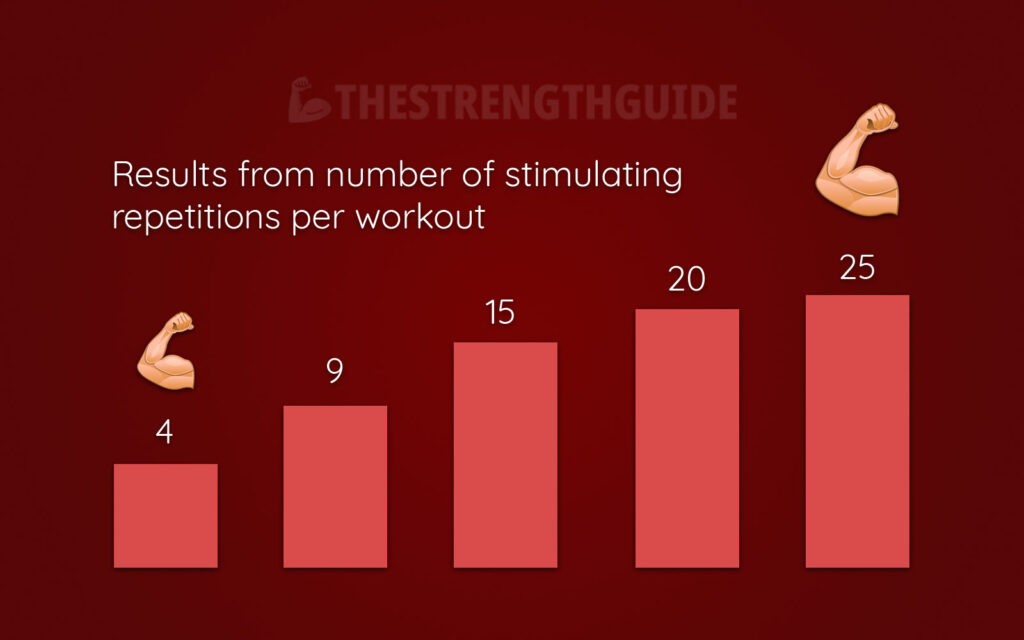

Fortunately, Chris Beardsley has done a great job with this article. Here he finds that the effect of different numbers of stimulating repetitions per session looks something like this:

So it looks like 25 is the optimal number, but 15 is not that much worse. It’s all about balancing the time spent in the gym, repetitions, and exercise enjoyment so that you get a sufficient number of stimulating repetitions.

A number above 25 will not give any additional effect, and at some point, the effect will actually get worse because you are overtraining. Exactly where the problems start will probably vary from person to person.

Chris Beardsley also highlights another interesting point.

The research shows that the difference in muscle growth is large when comparing, say, 3 versus 9 stimulating repetitions.

The differences become smaller when we compare, for example, 9 and 15 stimulating repetitions, and they disappear almost completely when we compare 15 and 21 stimulating repetitions.

So we get fewer benefits for each additional stimulating repetition we do after a certain point. After that, the extra energy is unproductive and essentially wasted.

In his work, Chris mentions that training 3 sets taken to failure with 5 repetitions might be the most efficient way to train in terms of energy expenditure.

That gives us 15 stimulating repetitions per muscle per set, which is almost optimal.

You shouldn’t necessarily train like that though.

It’s not just the number of stimulating repetitions you can achieve using the least amount of energy that matters.

You will learn more about this in the article on training intensity, as well as several other articles later in this guide where you will learn how to create your own training program.

One last thing: There is a difference between the training volume measured per session and the training volume measured per week.

As mentioned, your body stops responding to increased volume after a certain point in a training session. At that point doing more repetitions is not beneficial. You should instead go home and rest.

If your training program is properly set up, you’ll come back in a few days to train the muscle again. How many times you come back in during the week is determined by many factors which you will learn more about later in this guide.

The weekly training volume is the number of stimulating repetitions per muscle you have in total after a week of training. If you do 3 sessions with 15 stimulating repetitions, you will have achieved 45 stimulating repetitions that week.

The weekly training volume is the most important factor to control in order to get results from your strength training.

According to Chris, the upper limit for weekly training volume is likely around 75 stimulating repetitions, which would be equivalent to performing 5 sets until muscle failure for each muscle group, 3 times a week.

It is possible to achieve excellent results with a training volume below this level, and this method of training is not suitable for most people.

Pitfalls associated with stimulating repetitions as a measure of training volume

It is time to talk about some pitfalls linked to the concept of stimulating repetitions.

Specifically that it is not certain that all the repetitions you do are stimulating, even if you follow the guidelines above.

You can lift with seemingly maximal activation of the muscles and low lifting speed without getting an effect from the workout in certain situations.

How can this be?

Remember how the brain talks to the muscles via the nervous system? When lifting weights, the motor units in the body are activated by signals sent by the nervous system.

Sometimes, the nervous system can become fatigued, resulting in an inability to activate motor units linked to muscle fibers with large growth potential.

This phenomenon is called central fatigue.

Central fatigue occurs when the nervous system is no longer able to activate all the motor units needed to lift a weight.

There are various ways your sessions can negatively affect your nervous system, for example:

- Intense strength training with too short rest periods between sets

- Prolonged endurance training with too little rest before a strength workout

- Many sets and stimulating repetitions per exercise

- Training with a high number of repetitions per set

- Exhausting techniques such as drop sets, occlusion training, etc.

When central fatigue becomes an issue, maximum effort and low lifting speed will not produce the desired results.

The reason is that the weight feels heavy even if you are not using muscle fibers that have large growth potential.

The nervous system fails to activate the muscle fibers you want to use, and therefore they will not grow after the exercise.

Some sessions might therefore be completely wasted. You’ll learn how to avoid these problems later in the guide.

From this information, you can learn that there is an ideal training volume per week. That fact does not necessarily mean that a maximal stimulating volume per session is required.

You need to find the balance between volume per session and the number of sessions per week that give you good results while maintaining the motivation to work out.

Critique of stimulating repetitions as a measure of training volume

Well, it’s time to mention that not everyone in the industry agrees that we can simplify the concept of training volume as much as I have done here.

After all, the world would have been a very boring place if everyone agreed on everything. Therefore, I think we should take a little look at the criticism before we summarise.

Remember the article about why muscles grow? I mentioned that it is unlikely that metabolic stress has a massive effect on muscle growth.

The key factor is the number of stimulating repetitions per exercise or muscle group, not the amount of metabolic stress imposed on the muscles.

A study has been done that may seem to disprove this argument. Here, the subjects had to perform 3 – 5 sets to exhaustion at around 10RM.

One group had to perform a normal set until they could no longer lift the weight, while the other group had to take a 30-second break in the middle of the set.

The group that took a break in the middle of the set did not gain much muscle compared to the group that performed all repetitions without a break.

The researchers indicate that the group that took a break did not experience enough metabolic stress, and as a result, they did not gain muscle.

Is this really a valid conclusion by the researchers?

If we dive deeper into the study, we can see that they used a rest period of 1 minute between sets. This is not very much, and not enough for optimal muscle growth. You’ll learn more about that later.

Furthermore, we can imagine that the 30-second break in the middle of the set influenced how many stimulating repetitions the group managed to achieve.

Think of the group that trained normally. The first 5 repetitions of the set of 10 repetitions performed until muscle failure were not stimulating.

It was repetition numbers 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10 that stimulated muscle growth for this group based on what you have read so far.

The group that took a 30-second break in the middle of the set naturally did 5 repetitions that were not stimulating.

Then they got a break, allowing the motor units that had been engaged to recover. Then they did another 5 repetitions using the same motor units that had now had some time to relax.

They never got the chance to wear out the motor units that are easy to activate, so they did not get to use the muscle fibers with large growth potential.

Ergo, this group did fewer stimulating repetitions during the training period even though they also did 10 repetitions at 10RM.

What if they had also trained at a weight equivalent to 5RM so that all repetitions had been stimulating to begin with? Then I don’t think the 30-second break in the middle of the set would have had much to say.

This is of course just speculation on my part, but it shows that the theory of metabolic stress is not waterproof seen in the context of stimulating repetitions as a measure of training volume.

Another study found that a training volume of 16 sets per week is better than 8 if you train 2 times a week.

Doing a bit of math, we see that the researchers found that 160 stimulating repetitions per week are better than 80, which is quite contrary to the idea that 75 stimulating repetitions is the limit, and that fewer than that can still be very beneficial.

Diving deeper, we again see that the researchers used 1 minute of rest between sets. My theory is that the subjects did not get enough rest before each new set.

Because of that, the muscle fibers with the highest growth potential have already been fatigued, resulting in weaker muscle contractions.

This leads to less mechanical tension per set, and more sets are needed to achieve the same effect.

I think that if the researchers had used a 3-minute break, the subjects would have been able to lift more weight per set.

And if that were the case, I believe that 8 sets per session would be the upper limit for maximum muscle growth, which is also in line with the research referred to earlier in the article.

Other studies that used an extremely high training volume used sets that were not executed until muscular failure. But this would mean the training volume was not as high after all, defined as stimulating repetitions per session.

Chris Beardsley paints a good picture in this post on Instagram.

Despite studies that seem to show the opposite, 75 stimulating repetitions per week is likely the upper limit, and fewer repetitions will also give you great results.

Greg Nuckols is another researcher who has a good handle on strength training. He dabbles in powerlifting and coaching and has a monthly scientific publication analyzing studies in the field.

A lot of the criticism against the concept of stimulating repetitions comes from this article that Greg wrote.

As the article is quite lengthy, so I have taken the liberty of summarizing the most important points.

Greg believes that the idea that the last 5 repetitions before muscle failure are the ones that promote muscle growth lacks significant experimental evidence.

He is skeptical that we need to lift as heavy as 85% of 1RM or get within 5 repetitions of failure for the training we do to pay off.

At least when it comes to the large muscles involved in multi-joint exercises.

He cites a study that showed that the electrical activity of the muscles hardly increased when the weight increased from 50% to 90% of 1RM. Two other studies showed the same when the weight increased from 70% to 90% of 1RM.

He further writes that if one chooses to perform bench presses to train the chest or squats to train the quads, then all motor units could be recruited from the first repetition in a set of 12 repetitions taken to failure.

My comment here is that the subjects were instructed to lift explosively with full effort. We know from the previous article in this guide that the recruitment of motor units in the muscles is high at maximal effort regardless of lifting speed. But since the lifting speed is so high, it is hard for us to get much mechanical tension in the muscle fibers.

So these studies don’t actually tell us much about the amount of muscle growth we can expect after training at 50% of 1RM. They just tell us that the recruitment of motor units is high when lifting with maximal effort, something we already knew.

Greg goes on to say that he believes that the relationship between the weight on the bar and the activation of motor units is more complex for multi-joint exercises than what the theory of stimulating repetitions suggests.

He writes that it is not certain that muscle fibers must be exposed to maximum mechanical tension in order to grow after exercise. He believes this is contrary to either model-based research, long-term research, or both.

I think these are good points. The body is incredibly complex, and no one can say they know everything about this amazing machine.

So I guess I don’t really have any insights concerning this point. In practice, many studies seem to support the theory of stimulating repetitions, although not all do.

The answers will probably come soon via new research. Until then, we’ll just have to do the best we can with the information we have.

A lot of research seems to support the theory that there is a given stimulating number of repetitions per set. Certain studies appear to contradict the theory. The overall picture of the subject is complex and difficult to fully grasp.

Greg concludes by saying that it is obvious that some of the implications are reasonable, but he is a bit against the idea that it is “only the last five repetitions that count”.

He is, however, completely in favor of having to work close to muscular failure in almost any context he can think of. If you can do 12 repetitions at a given weight, you’re guaranteed to get a better effect from doing 3 sets of 10 repetitions than doing 3 sets of 3 repetitions.

Here I agree to a certain extent. As you learned in the article about how muscles work: some muscles reach full activation long before others. However, I don’t think this has a significant impact on how we should approach training in practice.

Greg believes that the number of hard sets per workout and per week is the most useful thing to track, even though it has its clear drawbacks.

Summary and a nice golden mean

Training volume is defined in many different ways both in research and in the industry at large.

Only training volume defined as the number of sets taken to failure correlates with muscle growth and strength.

This is because it is only that type of set that will consistently activate muscle fibers with large growth potential while the lifting speed is low.

Based on the research, we can say that not all repetitions in a given set are stimulating. It is likely that only the last 5-8 repetitions are critical for the results achieved.

To be on the safe side, we conclude that the last 5 repetitions are the ones that stimulate muscle growth.

Performing more than 25 stimulating repetitions per muscle per session will not give any additional effect, and 15 stimulating repetitions seem to be sufficient in many cases.

More than 75 stimulating repetitions per week do not seem to be necessary, and you can also get good results without doing as many as 75.

Even if you are lifting near muscular failure and at a low lifting speed, the training may be wasted if you find yourself in a situation where you are experiencing central fatigue.

This is because the nervous system fails to activate the muscle fibers that have large growth potential. It is only the muscle fibers that are activated that can grow significantly after strength training.

Not everyone in the industry agrees that it is only the last 5 repetitions in a set done to failure that matters.

I can agree with some of the criticism. Rather, it’s probably about “more stimulating” and “less stimulating” repetitions, and not that the last 5 repetitions in a set are the only ones that make a difference.

Still, I like the logic better than the proposed “number of hard sets per week”. The reason is that it is easier to control training volume based on what training intensity you have.

A hard set is a hard set, and nothing more than that. A set can feel hard and be 3 repetitions away from muscular exhaustion. It can also feel hard when you train to failure.

The difference between 3 repetitions short of failure and training to failure is large over several sets.

It is therefore easier to know whether to add or subtract sets if you count stimulating repetitions per session and per week.

You can then see how close you are to your target training volume, even if the training intensity is not always the same. This gives fewer sources of error to take into account when planning training programs.

A golden mean can therefore be to count the number of stimulating repetitions per session and week, but at the same time bear in mind that there is no exact number you have to achieve.

Keeping within 15 to 25 stimulating repetitions per session based on how often you choose to exercise per week would be a good strategy.

Then the number of sets you perform per workout per muscle will vary depending on how hard you train.

In my opinion, this is a more accurate method of measuring training volume than just counting the number of “hard sets”, and it is the best method we have to date for controlling our training volume.

by

by