You are now reading part 5 of the comprehensive strength training guide that teaches you the A - Z of building muscle and strength through articles that are easy to understand. Click here to see all the articles in the guide.

I feel pain from the tip of my toes to well above my lower back. The toilet seems very far away as I find myself standing looking down the stairs.

I guess I’ll just have to take it step by step and hope for the best. The handrail is creaking as I lean on it. Cramps force me to relieve my right foot from the weight of myself.

The trip down the stairs feels like a journey through purgatory. I swear to never train my legs again once I’ve finally made it to the toilet.

Sounds familiar?

This kind of cruel muscle soreness could last for over a week for me. It happened every time I missed a leg workout on the program I was following.

It was a bodybuilding program where I exercised every muscle just once a week. This meant that if I missed a day, it was two weeks between the sessions.

And that’s a solid recipe for muscle soreness.

Especially when I had to perform up to 12 sets per muscle ranging from 5 all the way up to 40 repetitions per set.

And yes, all sets were executed to total failure. It was maximum intensity for all it was worth.

This is obviously not a good way to train. Yet it has probably been done by most people who have wanted to start strength training.

After all, there are plenty of such programs out there. That does not mean they are particularly good.

A good training program balances intensity and training volume in a way that rarely gives you DOMS (delayed onset muscle soreness).

You may remember that you want to avoid both central fatigue and muscle damage that could limit the training effect.

A poor training program will make you train to failure in every set combined with too high a training volume, rest periods that are too short, and sometimes too heavy weights.

This is a recipe for long recovery periods according to research, something that will negatively impact your results.

So how hard should you actually train? To answer that question, we first need to define training intensity.

What exactly is training intensity?

Yes, what exactly is training intensity?

There are far too many measures of intensity, just like there are for training volume. We have absolute intensity, percentage-wise relative intensity, lifting speed as a measure of intensity, and subjective intensity.

And similarly to training volume, I think one of the ways of managing training intensity is better than the others.

Let’s go through them briefly first.

Absolute training intensity

Absolute intensity simply describes how much weight is on the bar.

Absolute intensity says nothing about individual differences or preconditions.

100 kg is 100 kg.

However, it can be very heavy for you and me, while it is seen as warming up weight for the world’s strongest man or woman.

Therefore, this is a poor measure to use when controlling the intensity of your strength training.

You learned earlier that 30 repetitions done to exhaustion build as much muscle as 5 repetitions done to exhaustion.

Therefore, the weight on the bar tells you nothing about the effect you get from the exercise. You and I can get very different effects from lifting the same weight for the same number of repetitions.

I recommend that you do not compare yourself with others and that you do not use absolute intensity as a way to measure your training intensity.

Training intensity as a percentage of 1RM

You can use a percentage of 1RM as a measure of training intensity.

For example, if you are able to lift 100 kg in an exercise, you can do 6 repetitions at a weight of 90% of your 1RM. In this case, it would be 90 kg.

This is a better measure of intensity than the previous one, and many high-level lifters probably use this in their programs.

Still, there are a good number of pitfalls here. If you use a percentage of 1RM as a measure of intensity, you are making a lot of assumptions about things you don’t really know that much about.

What if your daily form suddenly is worse than planned, and you can’t do all the repetitions?

What if your daily form is really good, and the repetitions feel too easy?

What about the individual differences between people in terms of how many repetitions they can do at a given percentage of 1RM?

In addition, as a beginner, you will get stronger very quickly. Should you retest your 1RM every two weeks and then adjust the whole program accordingly?

I don’t think this is a good measure of training intensity for people who are not involved in powerlifting as an elite-level sport.

There are definitely better alternatives.

Loss of lifting speed as a measure of training intensity

Do you remember that you need to train with maximum recruitment of motor units in the muscles while keeping the lifting speed low to get good results from your strength training?

When lifting with maximum effort, you will initially have a relatively high lifting speed. As the muscle fibers become exhausted, the lifting speed will gradually slow down, no matter how much effort you use.

This is what creates high mechanical tension in your muscles, which in turn triggers muscle growth and more strength.

Based on this, it is possible to use the loss of lifting speed as a measure of training intensity.

That is, you set a limit on how low the lifting speed should be before ending a set, without having any pre-set goal of the number of repetitions you need to achieve.

Several studies have used this way of defining training intensity with good results.

The reason it works so well is that the lifting speed is the same on the last repetition of a set done to failure as when you lift your 1RM in a given exercise.

Similarly, when you lift a weight you can only lift 2 times, the lifting speed during the first repetition is the same as when you lift the second to last repetition of a set done to failure.

The lifting speed will therefore tell you how close to failure your muscles are when doing strength training.

This will in turn reflect how much mechanical tension there is in your muscles as long as you are lifting with full effort.

Therefore, the loss of lifting speed during full-effort strength training is a very good measure of training intensity.

There is just one small problem.

How on earth are you supposed to know what your lifting speed is? Scientists use very expensive equipment when they do their studies.

The answer is simply that there aren’t many good ways to find out.

Yes, you can buy certain types of small devices that you can attach to the bar or your body. These use an accelerometer and other technological tools to estimate the lifting speed.

But they’re expensive and clunky, and they might be a nuisance during the planning, execution, and analysis of your training program.

A very good alternative is training with subjective intensity based on your own assessment of how far away from exhaustion your muscles are at any given time.

This is also the measure of training intensity I recommend you use when strength training.

Training with subjective intensity control, RIR, and autoregulation

If all the ways to control training intensity from before weren’t enough, there are also many ways to control the intensity subjectively.

I’ve seen everything from Borg’s scale, which is a scale that goes from 6 – 20 to RPE (Rate of Perceived Exhaustion) which goes from 1 to 10.

Personally, I like something called RIR (Reps In Reserve).

Research has shown that this way of controlling intensity can be more effective than training based on a percentage of 1RM.

Subjective intensity management based on the number of repetitions in reserve (RIR) is the method I recommend you use.

You have already learned that there are approximately 5 stimulating repetitions in a set taken to failure.

You’ve also learned that the weight you lift doesn’t really matter as long as you lift to failure within about 30 repetitions.

This allows you to manage your intensity well by estimating how many repetitions you have left before failure.

If you think you can do 2 more repetitions, but not 3, then you have 2 RIR. That is, you have 2 repetitions in reserve.

It doesn’t matter if you lift 10 repetitions with 50 kg on the bar when you could have done 12 repetitions, or 6 repetitions with 60 kg on the bar when you could have done 8 repetitions.

In both cases, you have 2 repetitions left in reserve, and the muscle-building effect of the exercise is the same.

You get exactly the same muscle growth as long as you have the same number of repetitions in reserve in the sets, no matter what weight you lift.

One potential drawback to keep in mind is that it is important to limit the number of repetitions to 30 or fewer, as doing more may decrease the effectiveness of the workout and make it more similar to endurance training.

If you stay within the 30-repetition limit, you will achieve the same results regardless of the weight on the bar, as long as you have the same number of repetitions in reserve when you train.

One advantage of using this method of controlling intensity is that it’s a form of autoregulation.

You’ll learn more about this in the article on how to make good progress in strength training.

In short, autoregulation means that during a period of training, you adjust the intensity based on your performance and capabilities.

This means that instead of pre-planning to add more weight, the individual can use their own performance and progress from previous sessions to adjust the weights at the appropriate time. This self-regulation allows for a more individualized and effective workout.

It also can provide added motivation and allows for flexibility to adapt to changes in daily form or performance, rather than having a rigidly structured workout plan that you might not even be able to follow.

Still, there’s an art to getting this right – but as I said, you’ll learn that later in the guide.

You need to practice subjective intensity control

I wish I could say that this is a perfect method for controlling the intensity and that everyone does it equally well.

Unfortunately, research indicates that beginners may not be very accurate in estimating how many repetitions they have left before reaching failure.

Fortunately, this is a trainable skill.

The more you practice, the better you get at it. Research shows that those who have been practicing for a while can estimate how many repetitions they are from failure quite precisely.

You should therefore try lifting to failure a few times so that you know how it feels.

Bring a training partner with you or ask someone at the gym if they can spot you. Don’t forget to warm up properly first.

Once you get good at estimating how many repetitions you have left before reaching failure, you will have a very good tool to control the intensity of your strength training in all repetition ranges and with all kinds of resistance.

How close to failure should you train?

Now you know that you can learn to estimate how close you are to failure and that you can use this to control the intensity of your training.

There’s just one problem. What exactly is failure?

Is it when you’ve executed the bench press to the point where your arms are comparable to a couple of flapping sausages?

Or is it when your training partner has helped you a little bit with 6, 7, or maybe 8 extra repetitions?

What about when you tear a muscle because you’ve pushed yourself through 10 repetitions with the technique of a 105-year-old person with osteoporosis?

Research has the answer to that too, thankfully.

In fact, studies on strength training do not typically use the term “failure” or “exhaustion”. Instead, the term “task failure” is more commonly used.

The point is that you are not in any way “exhausted” in the proper sense of the word. You are simply unable to carry out your task adequately any longer.

The task is to perform a strength training exercise with good and safe technique. Nothing more, nothing less.

Therefore, you have reached “failure” in an exercise when you are no longer able to lift weights with good technique – by yourself, without help.

For example, when you perform the bench press, your butt should be touching the bench and your heels should be touching the ground during all repetitions.

If on the last repetition, you have to change your technique by lifting your butt off the bench – well, then you’ve reached failure.

Thus you achieved an RIR of 0 in that set.

Similarly, during the deadlift, you will have 1 repetition in reserve if you have completed all the repetitions with good technique, but feel that you can only complete one more repetition with good technique before you have to start curving your back.

If you stop the set at this point, it gives an RIR of 1.

Failure is reached when you can no longer perform additional repetitions with proper and safe form without assistance.

The big question is whether it is better to push oneself to the point of failure during training or to stop short of exhaustion.

Studies in this area largely show that training a little short of failure gives the best results, although some research shows that you get better results from training all the way to task failure. Other research is not clear on what is best.

If we sum up the research, we can actually say that both can work.

I still recommend training a little short of failure. It’s both safer in terms of injuries and easier to recover from.

Remember that you will (hopefully) be strength training for many, many years to come. It should be fun to train, and pushing your body to the breaking point every time you exercise is not something I would call an enjoyable thing.

You’ve also learned that muscle damage is not good for your results, and that training closer to failure creates more muscle damage.

In addition, training closer to failure gives you more central fatigue, which again could affect how much effective training volume you actually manage to achieve during a session.

It’s suggested by research that training a little short of exhaustion is an effective strategy, instead of reaching “task failure” in exercises all the time.

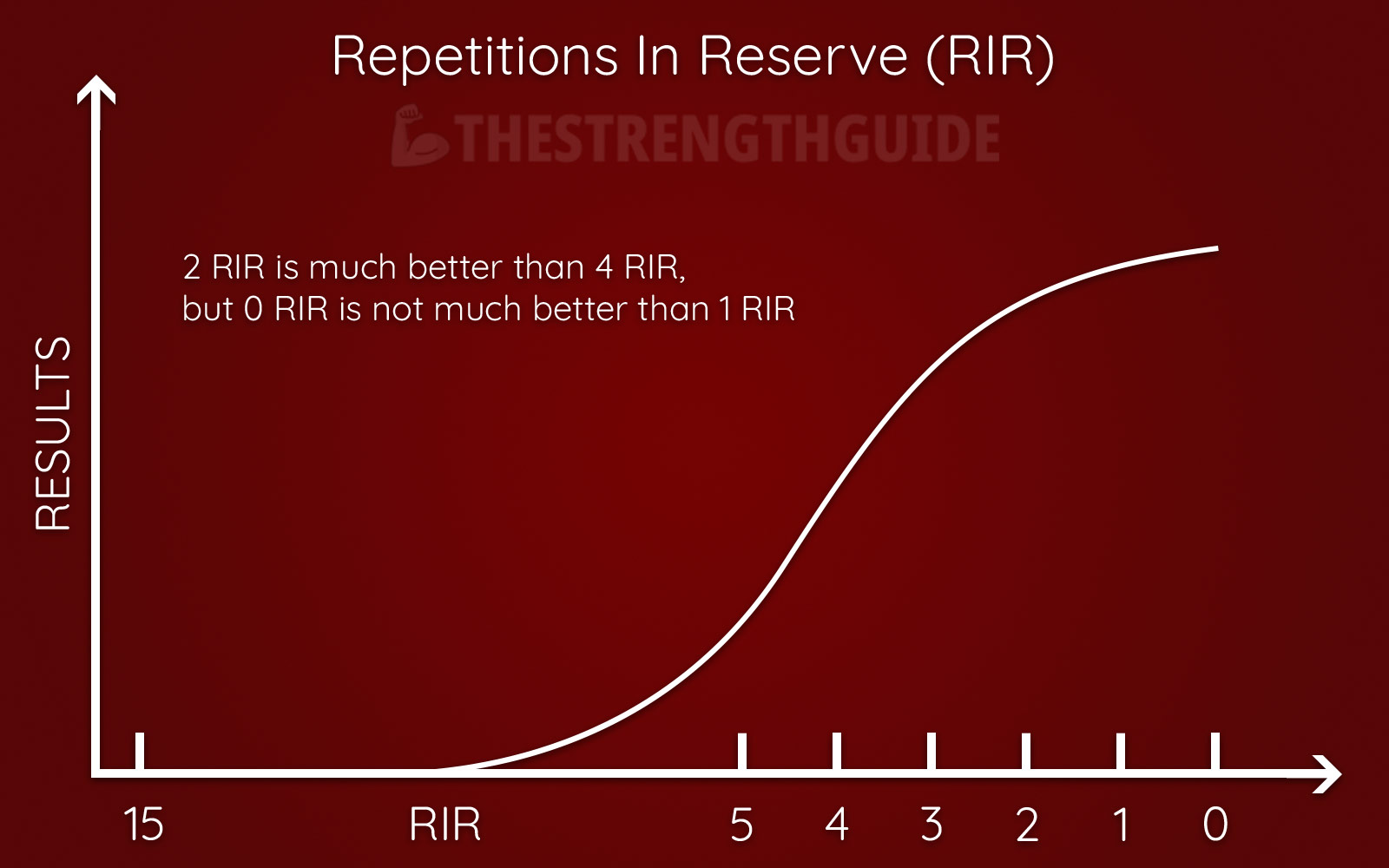

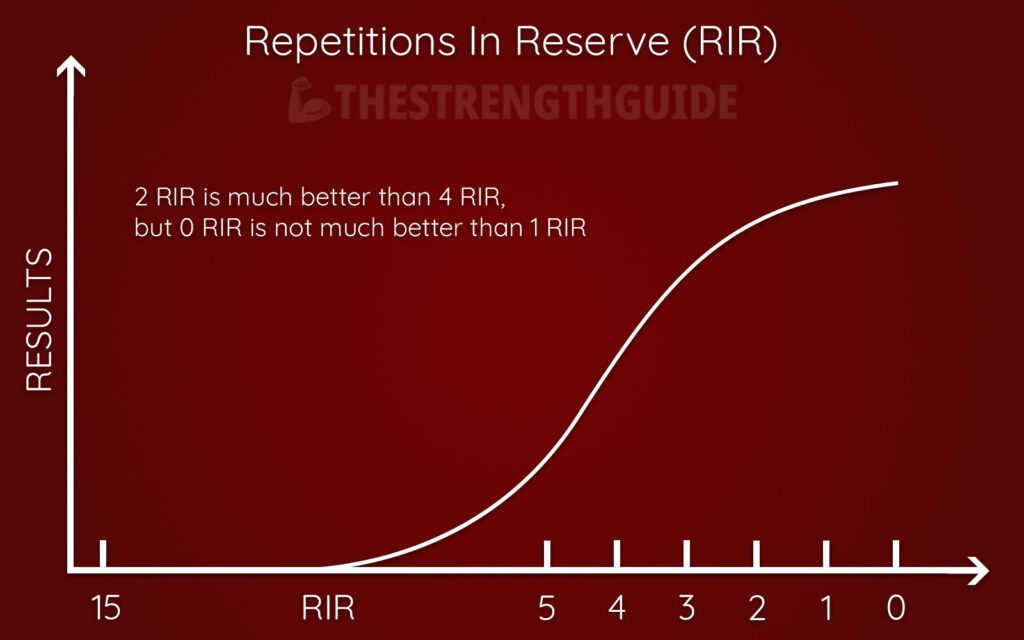

Similarly to training volume, the number of repetitions in reserve will give fewer and fewer benefits the closer you get to 0 RIR.

Thus, 1 repetition in reserve will be almost as effective as lifting to task failure, while 4 RIR will be much less effective than 2 RIR.

So, we can say that even if it is not necessary to train to failure, it will be necessary to get close in some way.

Does training status have anything to say?

An important consideration is how to adjust training as progress is achieved and strength is gained.

Should you continue to train with the same number of repetitions in reserve? After all, you can lift a lot more absolute weight, so you may find that it becomes too much for your body over time.

In the article about training volume, I wrote a bit about Greg Nuckols and his thoughts on the concept of stimulating repetitions.

He has also published some thoughts on training to exhaustion for beginners and more advanced practitioners. The article in question was published in MASS Research Review.

He also writes a bit about this in his article on stimulating repetitions.

In short, it seems that experienced people can train further away from failure than beginners.

We’re talking about well-trained people here, so this probably won’t be relevant until you’re approaching 3 – 5 years of solid and consistent strength training.

The idea is that well-trained people can fire up more motor units earlier in a set than beginners can. This is especially true for explosive training.

It is also the case that the demand on the body in terms of energy increases approximately linearly with increasing weight on the bar.

However, the density of mitochondria (the powerhouse of your cells) in the muscles does not increase very much with strength training. Nor does capillary density increase very much.

This means that the energy required to lift the weights increases as you get stronger, while the ability of the body to create this energy generally does not increase.

This can lead to failure earlier in a set for very strong people compared to beginners due to greater metabolic demands.

The idea is that well-trained people experience mechanical tension in muscle fibers that grow a lot after strength training at an earlier point, and therefore start their stimulating repetitions earlier during a set than untrained people.

Personally, I don’t think the research is clear enough on this, and I think that much of it is speculation.

This is also why I would recommend you train near failure even if you have been training for many years.

Maybe you can hold off on one extra repetition or experiment with days when you are further from failure than usual.

For most people, this problem will probably resolve itself given the amount of training experience you will have when it occurs.

If strength training is relatively new to you, or if you’ve been training off and on for periods, then you don’t need to think about this at all.

How to balance workout intensity and volume?

Well, we’ve finally come to the juicy stuff regarding the intensity of your strength training. Namely how you can best balance training intensity and training volume.

You might need to read the article about training volume to understand what you’re actually trying to achieve.

It’s really quite simple. When you are setting up your training program, you first decide on a certain intensity you want to train at.

Then you use your mathematical skills to work out how many stimulating repetitions this sums up to over the course of the session in the target muscle group that you’re exercising.

We’ll go into this in more detail in the article describing how to set up your own training program.

Nevertheless, let’s show a little example:

Simple mathematics tells us that in a set of 2 RIR, you perform 3 stimulating repetitions.

5 possible stimulating repetitions minus 2 repetitions in reserve is, after all, 3.

If you decide that you want to perform 4 sets of bench presses with 2 RIR, then you will have achieved a volume for the chest muscles of 12 stimulating repetitions.

Since you’ve learned that you want to be between 15 and 25 stimulating repetitions per muscle, you might as well do 2 sets of incline chest presses with manuals.

You’ll also train these with 2 RIR, giving you 6 extra stimulating repetitions. In total, you get 18 stimulating repetitions for the chest muscles, and can call it a day.

Another way to get enough volume is to rather do 4 sets of bench presses on 1 RIR, which gives 16 stimulating repetitions.

I recommend most people train with around 1 repetition in reserve. It is a safe and effective way to train and gives better recovery and effort throughout the workout than training to failure.

So, train to a point where you feel you most likely can’t finish the next repetition on your own, at least not the next 2. Then balance the number of sets based on how many stimulating repetitions you want to achieve during the workout session.

I should stress that many people do not train as hard as they think until they have had good practice in estimating RIR. When you feel that you can’t do any more repetitions without assistance, you will most likely manage 1 – 2 more.

If you had been paid 1000 dollars for every extra repetition you had completed with good technique, how many more repetitions do you think you would have squeezed out?

That’s how you should train until you really feel you can’t finish the next repetition.

Many people think they are training hard, but the truth is that they simply have too many repetitions left in the tank.

First, decide on the intensity you want to train at in terms of the number of repetitions from failure. Then multiply the number of sets by the number of stimulating repetitions you achieve per set. The number should be between 15 – 25 per muscle per session for the training to be effective.

Maybe you are now wondering how many repetitions you should perform per set. I can understand that.

It’s fair enough that you can take up to 30 repetitions per set and get good results. Still, it might be good to know if there is a number of repetitions that is best.

To answer this question, we need to look at the effect of training with many repetitions per set.

Do you still remember the concept of central fatigue that you learned about in the article on training volume?

When central fatigue occurs, the nervous system is no longer able to use your muscles efficiently. This will lead to poorer strength training results.

It appears that central fatigue increases with the duration of the work that is done in a workout. Since doing more repetitions takes longer, training with many repetitions will lead to more central fatigue.

So the lighter the weights you choose to train with, the more central fatigue will occur throughout the workout.

Therefore, even if you train with 1 RIR when doing 30 repetitions per set, you may achieve a slightly lower amount of effective volume during the entire training session than if you had done 6 repetitions per set.

By this, I mean that during the last sets, you may become exhausted due to central fatigue before you reach your 4 stimulating repetitions, even though it feels like you are training with 1 RIR.

You may also have to rest a bit longer before the next training session, which could affect your weekly training volume.

Therefore, it’s probably best to train in the range of 5 – 12 repetitions per set. If that sounds familiar, it’s not that crazy.

Bodybuilders train this way, and it’s most likely because this repetition range over time has been shown to give the most bang for your buck.

Training like this means you don’t have to waste energy doing lots of repetitions that aren’t stimulating. At the same time, it’s not so heavy that you’re always putting a lot of strain on ligaments and joints.

You also avoid too much muscle damage, central fatigue, and long recovery times. The best of both worlds in other words.

There is therefore no exact number of repetitions that is best, but rather a range of repetitions you should try to keep within.

Don’t try to hit on a precise number of repetitions per set.

Use repetitions in reserve as an indicator of when the set should end, and try to hit your planned RIR within the repetition range you have chosen.

For example, I always train at 1 RIR and try to hit this in the range of 5 – 8 repetitions. If you train this way, you avoid underestimating the number of repetitions you think you can do at a given weight.

You will also do more repetitions if you decide to continue until you know you can’t do another repetition, than if you decide in advance to do, say, 8 repetitions.

You will learn more about this in the article about progression and the article about how to train in practice later in the guide.

Summary of strength training intensity

There are many different ways to measure training intensity, and just as with training volume, there is one way that is better than the others.

I believe that subjective intensity control is the best method for most people. It requires no equipment, and research shows that you can get very good at this with a bit of practice.

You control the intensity of the session by estimating how many repetitions you have left in reserve, which is called RIR.

The research shows that it is most likely a bit better to train slightly short of exhaustion than to force yourself to task failure at every set.

My recommendation is to train until 1 RIR, i.e. that you lift until you are quite sure that you can only do one more repetition with good technique without help. Remember to train hard enough, and be honest with yourself.

This will give you 4 stimulating repetitions per set. You balance training intensity and training volume by multiplying the number of sets you take by the number of stimulating repetitions per set.

You should do between 15 – 25 stimulating repetitions per workout per muscle, which you can achieve by taking 4 – 6 sets of 1 RIR.

It is advisable to train in the range of 5 – 12 repetitions per set, focusing on RIR as an indicator of when you should end the set.

If you choose to train up to 30 repetitions per set, you will most likely experience greater amounts of central fatigue. This can lead to less effective volume during the workout and a longer recovery time.

Since you can choose your repetition range within certain limits, you suddenly have a freedom you rarely get with other training concepts.

You can add systems of sets and repetitions into your program that you want to try out, and you’ll get more enjoyment out of exercising.

If you’re looking forward to the workout, you will do the workout. And all exercise you do is better than the exercise you never do because you dislike it.

In fact, I would argue that sticking to a program that is only 20% optimal is much better than having a 99% optimal program that you end up not following.

And isn’t it the implementation, the actual doing, of strength training that is the most important thing?

by

by