You are now reading part 3 of the comprehensive strength training guide that teaches you the A - Z of building muscle and strength through articles that are easy to understand. Click here to see all the articles in the guide.

If you want to get stronger, you need to build muscle. Bigger muscles should be the main goal, even for the casual trainee. Then strength comes automatically.

That you can increase your strength as an athlete without putting on muscle mass is a myth.

It is not the case that bodybuilders are big and weak, while powerlifters have less muscle mass and are strong. Both bodybuilders and powerlifters are very strong and have very large amounts of muscle mass.

It’s just that powerlifters have specialized in a sport that is also technique-based. They are stronger in certain exercises because they have more training in those exercises.

In fact, some bodybuilders do high-level strength competitions during the “off-season”.

You need to train consistently over time to get good results from strength training. You have to make an effort week after week, month after month. You’ll gain a lot of muscle in your first 3 months, but the really big gains are waiting for you after 1 – 2 years of consistent training.

You may have learned that there can be several reasons why muscles grow as a result of strength training. Often these are mentioned:

- Mechanical tension in the muscles

- Metabolic stress in the muscles

- Hormonal response in the body

What if I told you that it is very likely that only one of these factors plays a significant role? Suddenly it’s much easier to create workout programs that work.

In addition, you’ll avoid accounting for a whole lot of confusing words and expressions that neither I nor you would be able to pronounce anyway.

Let’s take a closer look at the factors I think don’t matter before we get to the mechanism I think is the real hero – namely mechanical tension in the muscles.

Metabolic stress after strength training

Metabolic stress has been mentioned in the training industry as a prominent cause of muscle growth.

In short, metabolic stress occurs when waste products build up in the muscles during exercise.

According to theory, these waste products should signal to the body that the muscles are too small to handle the stress they are exposed to. The body should then, apparently, want to increase the size of the muscles.

Metabolic stress is brought up as the reason why training to the point of muscular exhaustion with up to 30 repetitions per set, seems to be as effective as heavier strength training for increasing muscle size.

Metabolic stress is also mentioned as the reason why occlusion training, i.e. training that cuts off the blood supply to the muscle, is equally effective.

In this case, I don’t think metabolic stress plays a major role, which is something we will come back to soon.

First, I will take a look at some of the arguments used to “prove” that metabolic stress causes muscle growth, and why this is not necessarily true.

1 – Metabolites create exhaustion that stimulates muscle growth

When a muscle gets more and more fatigued, metabolites tend to build up. The argument is that these metabolites create fatigue, which in turn signals and stimulates muscle growth.

The counter-argument is that metabolites are not necessary for this exhaustion to occur. Research shows that local muscular fatigue during eccentric exercise can occur without much accumulation of metabolites.

Therefore, metabolites are only one of many possible causes of fatigue. The fact that they correlate does not mean that the accumulation of metabolites causes muscle growth.

A more likely explanation is that the metabolites that cause fatigue are involved in creating increased mechanical tension in the muscle. We will come back to how this happens.

2 – Lactic acid can cause muscle growth

Lactic acid, or lactate, has been linked to increased muscle growth in a mouse study. In this study, lactate was given to mice, which responded by gaining larger muscles.

So you might think that exercising in a way that produces a lot of lactic acid build-up would be helpful for muscle growth. Lactic acid accumulation is a form of metabolic stress, after all.

However, this does not seem to be true. Another study found that a higher amount of lactate in the muscle led to lower signaling linked to muscle growth.

Lactate is also transported throughout the whole body. So you would think that a high lactic acid build-up in one part of the body would cause muscle growth in muscles that are not directly trained. I haven’t seen any research showing that this can happen.

We actually see large amounts of lactate in the muscles after high-intensity interval training. These amounts are quite similar to those produced by strength training. Despite this, high-intensity interval training does not produce significant muscle growth.

If lactate had caused muscle growth, we would expect all the muscles in the body to have increased in size after training only one muscle. We would also expect to see significant muscle growth after high-intensity interval training.

In the research, we see none of this, which suggests that the build-up of lactate in the muscles is just a random effect that correlates with other mechanisms that create muscle growth.

3 – “Pump” in the musculature creates muscle growth

Many in the older generation of bodybuilders considered the so-called “pump” in the muscles to be an important driver of muscle growth. Arnold, after all, had the famous statement that it was better than an orgasm. His words, not mine.

“Pump” refers to the feeling you get when you experience swelling in your muscles during a workout. This feeling tends to occur more often when you train with lighter weights and more repetitions.

A study published in January 2020 describes that it is metabolic stress that creates the so-called “pump”, or muscle swelling. The researchers explain that metabolic stress is thought to contribute to muscle growth.

They found that people who had a greater amount of swelling in the muscle after the first training session also had greater muscle growth at the end of the study. This may be a convincing argument that people who experienced more metabolic stress had greater muscle growth.

Nevertheless, I think there are some weaknesses in this study.

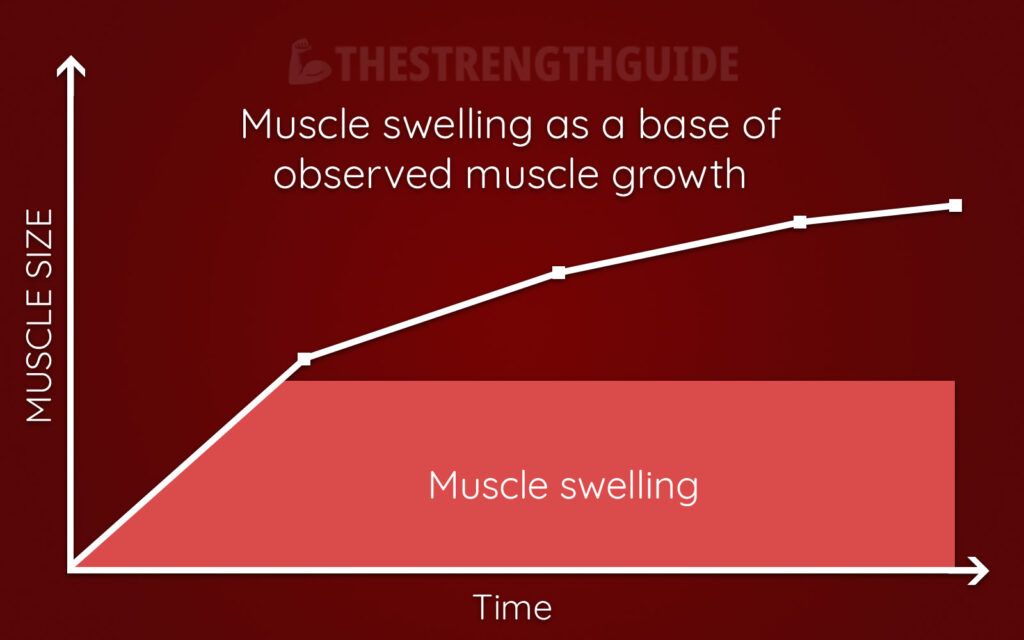

Firstly, the last test was performed 3 – 7 days after the last training session. Research shows that muscle swelling can last for over a week after a training session, which may have affected the results.

Theories have also been put forward that muscle swelling peaks and remain stable over a training period. In a way, the swelling constitutes the base of the muscle growth we observe.

Illustration based on this science commentary.

Therefore, it may well be that those who experienced more muscle swelling at the start of the study also had more muscle swelling as a base when the last test was done.

It could also be that those who got more muscle swelling were the ones who managed to push themselves more during training. Thus, they may have trained harder, which may have led to greater muscle growth.

Based on this study, I don’t think you can say that muscle swelling is a driver of muscle growth because it correlates with metabolic stress.

It may well be the case that more swelling in the muscles indicates greater mechanical tension in the muscles, which in turn leads to better results. This is because of the mechanical tension, and not because of the muscle swelling itself.

As mentioned earlier – the fact that something correlates does not mean that one causes the other.

In short, there is not adequate support in the scientific literature for metabolic stress as an instigator of muscle growth.

There is either a lack of support for metabolic stress leading to muscle growth or other explanations that are better. These explanations all point back to the possibility that mechanical tension in the muscles is the main cause of muscle growth.

Hormonal response after strength training

Strength training can lead to an increase in levels of growth hormones and testosterone in the body.

Since we know that anabolic steroids work very well when you want muscle growth (that not being a reason why you should take them), it might be natural to think that this hormonal response is also responsible for some of the muscle growth you see.

Without going too much into the complicated theory, this does not seem to be true. The reasons are quite similar to those we went through for metabolic stress.

The body’s hormonal system is very tightly regulated. Hormones such as testosterone and growth hormone are important for muscle growth and a bunch of other functions in the body. However, an increase in these hormones after a training session has no bearing on the results.

Of course, you need to sleep well at night, be well rested and keep your stress levels down to limit negative effects on hormonal balance.

But planning all your training around getting the best possible hormonal response? You might as well let that idea die right now.

Your body is a very well-regulated system, and studies show that normal ranges of hormones in the body do not affect muscle growth.

So even though levels of growth hormone and testosterone increase after exercise, you would get just as good an effect from exercise without this increase.

The increase in hormones is correlated with muscle growth but is not the factor that causes it.

So spend your time caring about the factors that matter. Don’t push yourself through 20 sets of 20 repetitions of heavy squats because some guru on the internet has said that it quadruples your growth hormone.

Don’t think that doing squats will build muscle throughout your whole body because of hormone secretion. As mentioned, I have not seen a single study that has been able to show this.

Focus on the one factor we undoubtedly know affects muscle growth and increases in strength, namely mechanical tension.

Mechanical tension in the muscles

As humans, we have done a lot of research that unfortunately has been to the detriment of other living species.

This is sad, but it has also helped us increase our understanding of many complex processes in the body without having to do unethical things to other people.

Among other things, we have done studies on birds where we have attached weights to their wings in order to see what effect this has had on their muscle mass.

Leaving aside the animal abuse aspect of this, there have been many exciting results from this type of research.

In 1995, a study was carried out on birds showing what mechanical tension in the musculature can do for muscle growth. And remember: more muscle mass makes you stronger.

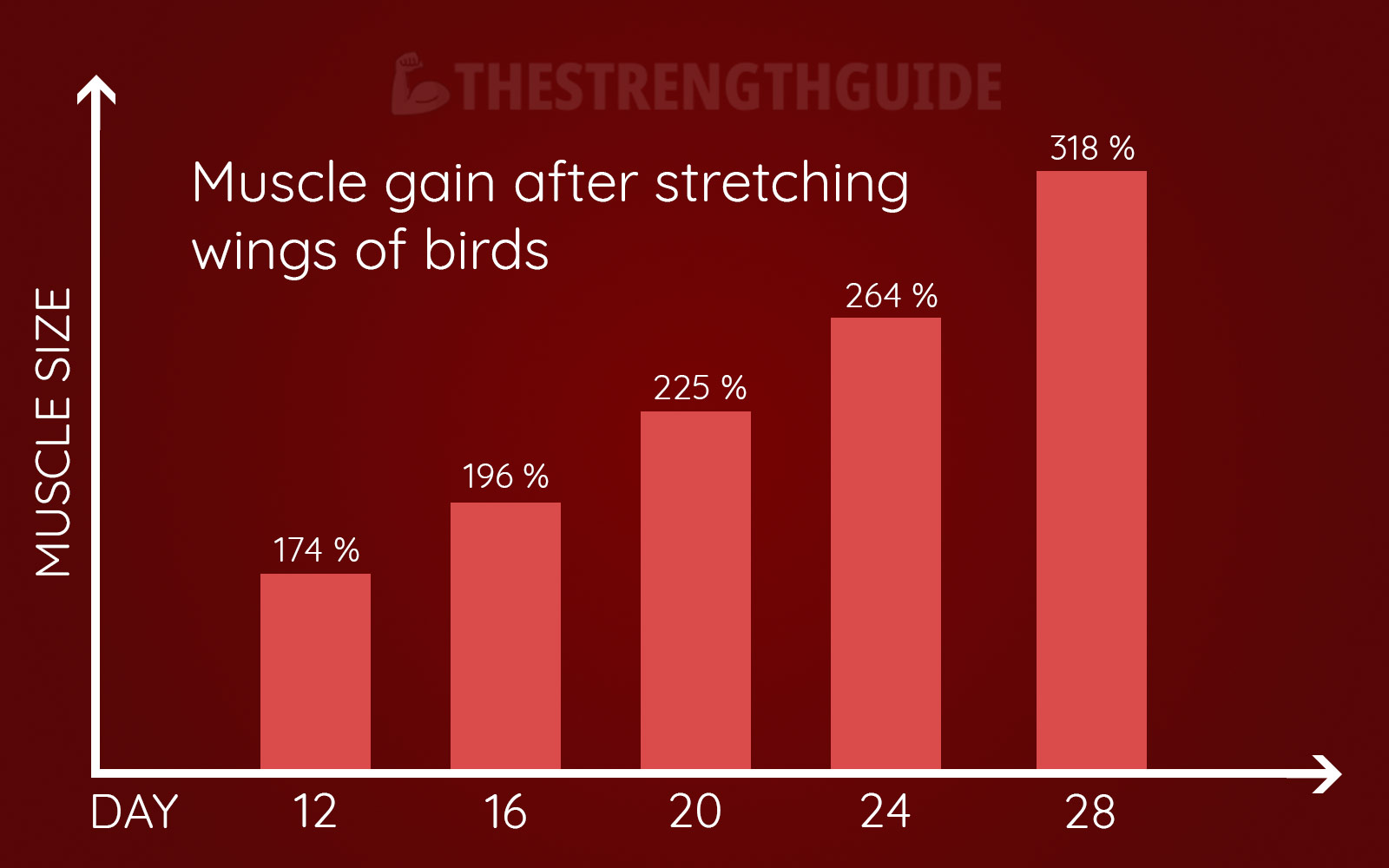

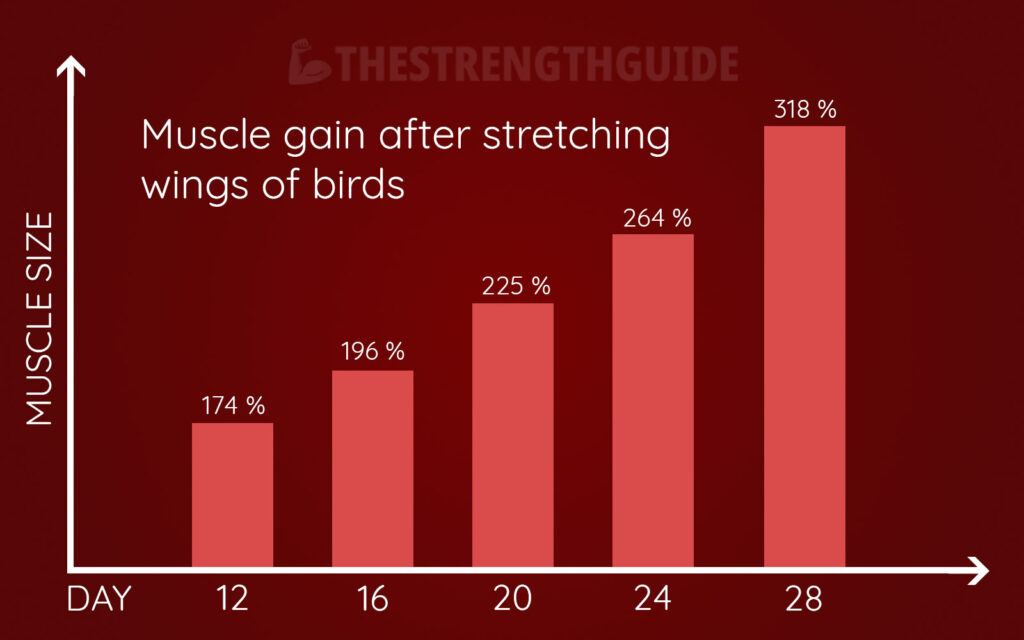

The researchers hung weights from the birds’ wings and looked at muscle mass after 12, 16, 20, 24, and 28 days. After just 12 days the muscle mass had increased by as much as 174%.

After a mere month, muscle mass had increased by an incomprehensible 318%.

Thus, the mechanical tension in the muscles gives a strong signal that the muscles must grow and become stronger. We can apply such mechanical tension to our own muscles through strength training.

Mechanical tension is a force that affects a material when it is being stretched, or when it resists stretching. When we exercise, our muscles resist stretching from the weight we lift.

The signal that the muscle is being affected by mechanical tension comes from a so-called mechanoreceptor that is attached to each muscle fiber.

Think of the mechanoreceptor as a small sensor that sends a strong signal to the body that the muscle needs to grow to cope with the stress it’s undergoing.

The weight you lift doesn’t matter

Let’s take a look at the types of mechanical tension that matter for us who want to make progress in our strength training. This is very important to understand:

The amount of weight you lift has little bearing on your results.

I know it may seem a bit strange that the weight is insignificant. Earlier in this guide, we talked about the fact that you have to lift heavy to get results from strength training.

That’s true, but we need to define what “heavy” means. And I’m not talking about the weight you’re lifting, but about what’s going on inside your muscles.

The mechanical tension in the muscle as a whole has little to do with muscle growth.

Let me try to explain. Imagine that your 1RM in the bench press is 100 kg. You put 50 kg on the bar and do five repetitions.

This feels easy. The mechanical tension in your muscles in total is not particularly high.

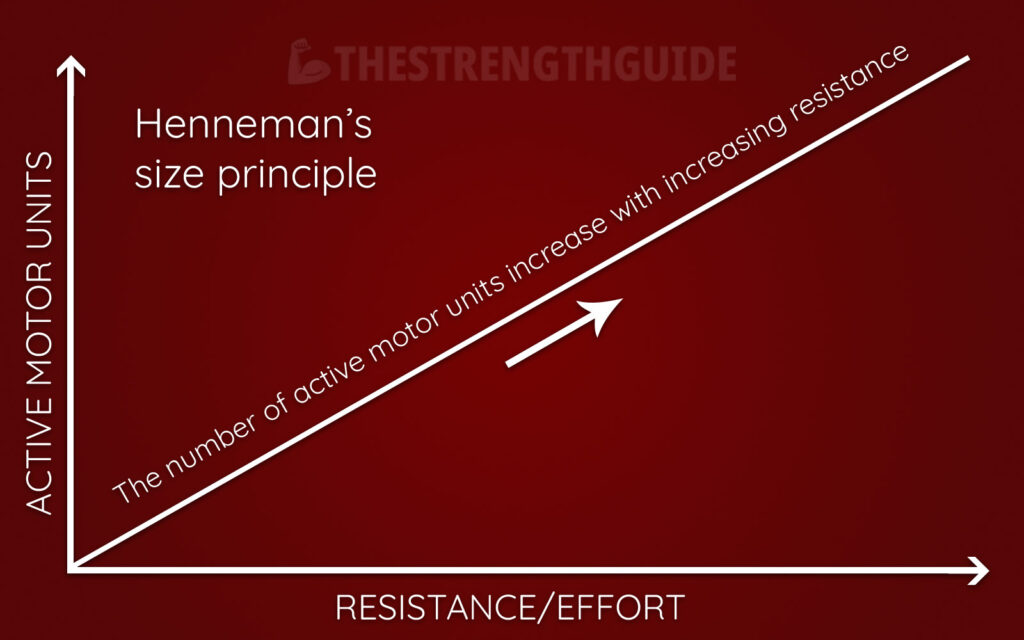

In fact, you won’t even activate very many motor units. At least not the ones with the greatest growth potential, as you may recall from an earlier article in this guide.

You probably also remember that a single muscle fiber is either off or on. So the muscle fibers you actually activate when you lift 50 kg experience extreme mechanical tension.

50 kg is very “heavy” for the muscle fibers that have to work. The problem is that they have already reached their maximum size, so we get no effect from the exercise.

It is the individual muscle fibers that experience mechanical tension, not the muscle as a whole. It is only the muscle fibers that are activated that experience mechanical tension.

Hold on for a second, you may think. Why does this really mean that the weight you lift is of no importance?

That’s a good question, and it’s actually a bit misleading to say that the weight doesn’t matter. We will come back to this in a later article in this guide.

The weight is significant for how you structure your training, but it doesn’t matter on a microscopic level in the body. The muscles have no idea how much weight is on the bar.

It’s not the weight we lift that creates the mechanical tension. It’s actually the muscle fibers themselves. Even training without external resistance can have positive effects.

When we train with weights, the muscle fibers will experience mechanical tension as they try to shorten themselves while facing resistance.

This fact has led many to believe that only heavy weights create enough mechanical tension for muscles to grow and get stronger. Light weights can’t have the same effect, right?

The fact that we experience muscle growth when we train with light weights is explained by theories of metabolic stress and hormonal response.

This is a fallacy. Both heavy and light weights can create considerable mechanical tension in muscle fibers, which in turn will make them grow. To understand this, you need to know about something called the “force-velocity relationship”.

The force-velocity relationship and mechanical tension

I can understand that this might be a bit complicated. When things get too complicated, it can be a bit boring to try to keep up. I will therefore simplify this as much as I can.

It is important that you understand this to discover how strength training can make your muscles bigger and stronger. This knowledge will influence how you create training programs, and also how you train in practice.

So hang in there!

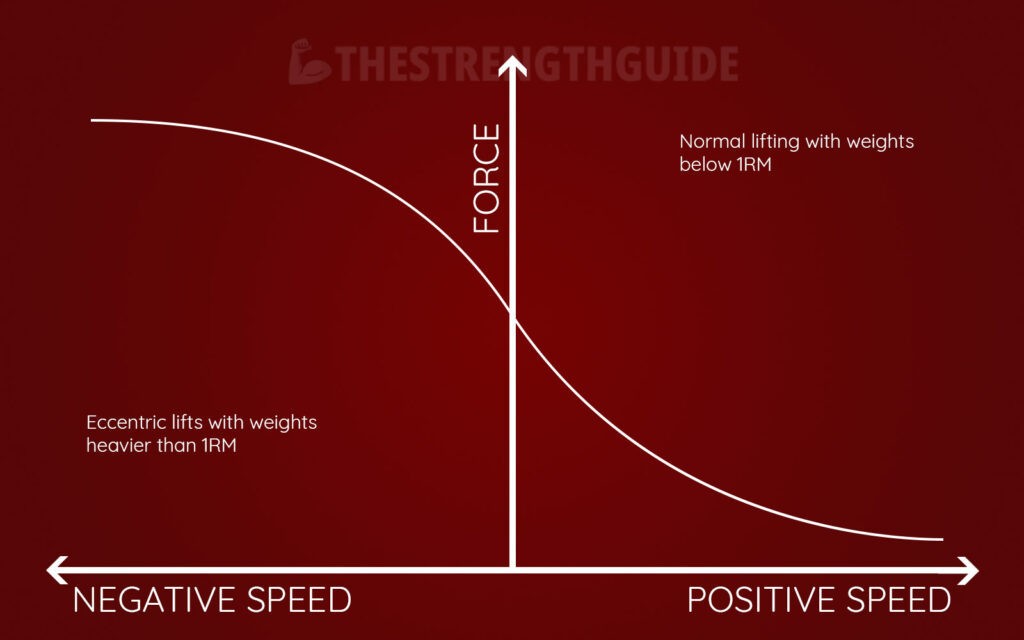

The force-velocity relationship is just a curve that looks like this:

When you lift a given weight very fast, your muscle fibers are not able to produce very much force. This leads to little mechanical tension in the muscle fibers.

On the other hand, if you lift a weight slowly, your muscle fibers will produce a lot of force. This will again create large amounts of mechanical tension.

If you put on more weight than you can lift, you will have to slow the weight going down (lest you get crushed). This method of training is called eccentric training and creates a large force output and negative lifting speed.

So I guess you just have to lift light weights very slowly to get the best possible effect from the training for the least possible effort?

Not so fast.

When you lift light weights slowly, you’re only using a fraction of your musculature. The muscle fibers you are using are experiencing high mechanical tension, but they have already reached their maximum size through daily activities.

To get the maximum amount of mechanical tension in the muscle fibers that matter, two things have to happen simultaneously:

- You must achieve a slow lifting speed

- You must achieve a high level of effort

Lifting light weights slowly fulfills the first criterion, but not the second. Lifting light weights quickly fulfills the second criterion, but not the first.

To meet both criteria, you can lift a heavy weight so that the lifting speed is automatically low, even if you use maximal effort.

You can also lift light weights so many times that the muscle becomes fatigued. Then you suddenly have to increase your effort considerably as it gets heavier and heavier.

Then the lifting speed will gradually go down due to the exhaustion the muscle experiences.

Lifting speed, perceived effort, and effect of training

I think we need to dive just a little deeper into this topic. This will make your understanding better, which is great news for your results.

If you read the article on how muscles work, you probably understand the deal with muscle fibers.

You know that when you start the first repetition with heavy weights, you will activate most of the motor units in your muscles. Even those that are difficult to activate, which are linked to muscle fibers that grow a lot after strength training.

If you use light weights, you will initially only activate motor units that mostly control type 1 fibers. These do not grow as much, since they are used extensively in everyday life.

Let’s go back to the example where you bench press 50 kg. This is just 50% of your 1RM at 100 kg. You will be able to lift this weight about 30 times.

The first 15 repetitions will feel relatively easy, don’t you agree?

Then they will feel heavier and heavier, and from repetition 25 it will be very hard to lift the weight. The last repetition will actually feel as heavy as if you had lifted 100 kg once.

Let’s declare it one more time: the 30th repetition with 50 kg on the bar feels as heavy as the first repetition with 100 kg on the bar.

But the weight hasn’t changed, so what’s going on here? Why is it like this?

Do you remember Hennemann’s size principle from the article about how muscles work? Then you might also remember that the body only activates the muscle fibers that are needed to do the work that needs to be done.

When you first start lifting 50 kg, you activate the motor units that are mainly associated with type 1 muscle fibers. But they cannot last forever. At some point, they will wear out.

At this point, metabolites that build up in the muscles will hinder the muscle fiber’s production of force. The same thing happens during, for example, occlusion training.

When the body notices that it is unable to provide enough force to lift the weight, more motor units are activated.

Eventually, the motor units that are most difficult to get hold of are also activated, and so are the muscle fibers that grow most after strength training.

The metabolic stress will therefore indirectly create mechanical tension in the muscle fibers that have a high growth potential. This happens because they have to step in when the other muscle fibers are worn out.

This is also the reason why the last 5 repetitions of a set of 30 repetitions to failure feel as heavy as a set where you lift heavier weights and only manage 5 repetitions.

Do you remember that we have a small sensor on each muscle fiber, a so-called mechanoreceptor?

It’s the mechanoreceptors on the muscle fibers that are difficult to get a hold of that you want to activate.

This can only be done by lifting heavy enough, or by lifting close to failure with lighter weights.

What about muscle damage (micro-tears in the muscle)?

I remember when I was a young boy who had just started learning about strength training.

I read a lot. For hours I could sit in my room completely lost in Google searches. Searches that would take me to many websites with strange advice that didn’t quite have roots in reality.

Almost all of these pages explained muscle growth with a now outdated theory.

Namely that the muscles are damaged during strength training due to mechanical tension. That they get microscopic tears which are then repaired, making the muscle bigger and stronger.

That sounds good, I guess. That you break something down so that it can grow and become stronger.

Unfortunately, the research doesn’t support this theory.

Studies have been done that show that the amount of muscle damage is not related to muscle growth.

If muscle damage is a pathway to bigger muscles, then you should see increases in muscle mass after microscopic muscle damage in the absence of mechanical tension. This is not the case.

Therefore, it is probably safe to assume that you do not need to injure muscles for them to grow. In fact, I’m going to go out on a limb here and say that you should avoid too much muscle damage in general.

After workouts that create a lot of muscle damage, the muscles will take longer to recover. Maybe the potential muscle growth is finished long before you are ready for a new workout.

It’s silly to wait for the muscle damage to be repaired before you can train again.

So make sure you stimulate all your muscle fibers enough to give them a reason to grow, but not necessarily much more than that. This is a good strategy for building muscle and strength.

Later in this guide, we’ll go through how you can put this into practice.

Summarizing and simplifying complex theory

Metabolic stress, hormonal response after exercise, and microscopic tears as part of muscle damage most likely don’t have much influence on muscle growth.

Muscles grow and become stronger mainly due to mechanical tension in the muscle.

It is not the muscle as a whole that experiences the mechanical tension, but the individual muscle fibers that are activated.

The mechanical tension is sensed by a mechanoreceptor attached to each muscle fiber as it attempts to shorten against some form of resistance. This creates a considerable force in the muscle fiber.

Both heavy and light weights can create muscle growth, as long as all our muscle fibers are activated while the lifting speed is low.

You can ensure this by training close to failure with light weights, or by training with heavy enough weights that you activate all the motor units that are difficult to get a hold of from the first few repetitions.

Muscle damage should be avoided because it prolongs the time between each possible training session.

I think it’s useful to simplify complicated theories. If you have a simple framework to deal with, then it is not important to know exactly what is happening at the cellular level in the body.

Maybe for scientists, but not for you and me.

That’s why I don’t think it’s particularly important whether metabolic stress or hormonal response can affect muscle growth after strength training.

It is more important that we know that mechanical tension absolutely does. We can use that information to build training programs based on the concept of mechanical tension to achieve our goals.

If we also get some muscle growth as a result of metabolic stress, then that is a side effect we can happily deal with.

We will go through what this “simple framework” can be later in the guide. Specifically in the article about training volume, as well as in the article about training intensity.

by

by